March 11, 2024 by Becky Stevenson, Ashley Norris, Clarissa Ayala and Victoria K. Smith

Campus Safety: Federal Requirements, Navigating College Resources, and a Survivor’s Journey to Advocacy

Becky’s Story

In the national discussion centered around campus safety, one name has remained hidden: Becky Stevenson. Her violent assault preceded those revealed by the 2016 university scandal that made national headlines. When media inquiries came in, it was unsafe to use her real name, so she advocated for others using the alias, Jane Doe. The now 28-year-old Lone Star Legal Aid attorney comes forward to share the story of her journey from survivor to advocate.

The Fraternity Party

Becky Stevenson was a college student, a sorority sister, and by all definitions, a “good Southern girl.” On the night before her 19th birthday, she went to a fraternity’s party. It was 2013 and the theme was “America,” so she dressed in a red fit-and-flare dress, pearls, and the confidence of Jackie O., to enjoy what she thought would be a classic college experience. “[I wanted to] have fun with friends, get drunk, maybe make out with a cute boy, and wake up with a hangover,” she recounted. “I had the perception that rape was exclusively committed by gross-looking predators, lurking in alleys and parks at night. No way could this happen at a friendly fraternity party.”

Becky Stevenson

I had the perception that rape was exclusively committed by gross-looking predators, lurking in alleys and parks at night. No way could this happen at a friendly fraternity party.

After several shots of liquor, some of the fraternity’s signature spiked punch, and a failed attempt at shotgunning a beer, Becky began to vomit. Fraternity brothers offered her more of their punch as a remedy. Then, everything went black.

A few hours later, Becky woke up naked, in pain, and laying in a pool of her own blood. She put on her dress, but her underwear and pearls were missing. On her way out, she began vomiting again, this time with blood. It appeared as though she was the only person on the property. She stumbled home down a dark road, checking texts from concerned friends.

Becky recalled the aftermath: “I felt disgusting, like I needed to clean my body, so I took a shower. I remember seeing blood trickle down my legs. I was in a world of pain. The shower didn’t make me feel cleaner. As I reflected on my nakedness I noticed bite marks that had broken my skin, boil-type marks or burns on my thighs, and abrasions. Walking was painful. What happened to me? I felt engulfed with apprehension. Did I want to know? Was this normal? Why was I bleeding so much?”

Attending church that Sunday morning, Becky had a revelation that something horrible happened to her. She just couldn’t pinpoint specifics. She was turned away from the university’s health center and a women’s health clinic when she tried to get medical care for sexual assault. “We don’t do that here,” she was told.

The SANE Exam

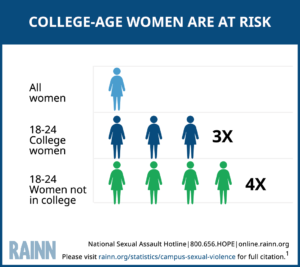

Source: RAINN

The nurses at an off-campus urgent care center informed her that she needed a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) exam, and this could only be performed at an emergency room. Alone but brave, Becky walked to the receptionist at the ER and requested a SANE exam. She told her story to each new person who entered the room: the attending, the insurance person, the officer, the nurse. They questioned why she showered and why she didn’t bring the clothes she wore that night. Then, it was time for her examination.

Becky recounted the excruciating details of her SANE exam, starting with the photos the nurse took of her naked body as she swabbed for DNA from her legs, breasts, arms, back, hands, neck, face, and chest. Becky was told she would undergo a Pap smear. Raised in a sheltered environment and wanting to remain a virgin until marriage, this was something she had never even heard of. As the nurse snapped photo after photo, an advocate from the Advocacy Center for Crime Victims and Children held Becky’s hand.

“I’ll never forget how much I’d hoped that the SANE nurse would tell me nothing serious had happened, how naively I clung to that hope through the entire procedure, and how shattered I felt when the SANE nurse looked me in the eye and told me she’d found significant signs of sexual assault,” said Becky.

Not only had Becky been sexually assaulted, the nurse characterized the attack as “remarkably unorthodox.”

“She didn’t think it could’ve possibly been one person because of the amount of semen, amount of tearing, amount of blood, and how mutilated my body was,” said Becky. “At this point, I was more willing to imagine that I’d agreed to this than that someone disregarded my humanity and raped me that night. For over an hour, I wept so hard that the only sentences I could physically articulate were ‘I hate them. My body is ruined. No man will ever want to marry me.’ I wanted to stay a virgin.”

The Police Report

Becky was adamantly opposed to filing a police report at first, thinking it would just cause trouble. Once the reality of the situation sunk in, she decided reporting was her best option for justice. Although the school informed members of the fraternity that they were under investigation, university officials told Becky they wouldn’t begin their investigation until the results of the rape kit came back, a process Becky assumed would take a couple of weeks. As Becky waited, news of her assault spread throughout campus.

Source: RAINN

“Everyone was talking about it,” recounted Becky. “The retaliation that I experienced was endless and went on for a year and a half. At the time, the university did not have a Title IX office, so there was no support available to help protect me.”

What is Title IX?

Title IX was enacted over 50 years ago to prohibit sex-based discrimination in all educational institutions across the United States that accept federal funding. This means any institution accepting any type of federal funding, including student federal loans, must follow the law. This requirement includes private and religious colleges. Title IX ensures that educational programs and activities are operated without discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Survivors of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and other forms of sexual violence or misconduct are prohibited and survivors are supposed to be protected from retaliatory acts.

In the past, how colleges deal with campus sexual assault often relied on how they saw Title IX rules, their financial connections, and their desire to avoid negative publicity, rather than a clear dedication to keeping students safe. Sexual misconduct in college is a serious issue because people don’t always understand consent, and there’s a generational trend of not respecting others’ bodily rights. So, it’s crucial for colleges to not just meet the basic Title IX rules but also actively promote survivor-focused policies that clearly outline what behavior is acceptable. This way, we can work towards creating a safer and more supportive environment for everyone.

Dealing with campus sexual misconduct in Texas colleges isn’t the same everywhere, as shown by the mix of information on different websites. The most helpful sites have well-staffed Title IX offices, clear guides on how to report, lists of local resources for survivors, mandatory training for everyone on sexual assault, dedicated response teams, advice on supporting a friend who’s been through it, public announcements, and info on filing complaints with the Office of Civil Rights. Unfortunately, some sites have incomplete info on Title IX, don’t say much about their staffing, blame survivors, label sexual assault as “Non-Title IX Misconduct,” or don’t mention it at all.

At a minimum, Title IX compliance at a college or university requires:

- At least one qualified Title IX Coordinator with clearly listed name, email address, and phone number online;

- Policies for how to handle reports and investigations, and policies published online;

- Regular educational trainings and prevention programs to educate students, faculty, and staff about sexual misconduct, consent, bystander intervention, and their Sexual and Interpersonal Misconduct policies;

- Immediate support to survivors, like counseling, accommodations, and safety measures;

- Prompt and thorough investigation of reports of sexual misconduct in a manner that is fair and impartial;

- Confidential reporting options for survivors if they do not wish to proceed with a formal investigation;

- Disciplinary action against students who commit sexual assault, as well as those who retaliate against the survivor;

- Private records of all reports, investigations, and outcomes;

- Collaboration with local law enforcement to ensure the student is aware of their legal rights and options;

- Open communication with the survivor throughout the process;

- An appeals process for both parties to challenge investigations if new evidence arises or procedural errors were made; and

- Publishing a document every year disclosing the number of reports filed and their outcomes.

Becky did not receive the benefit of those protections when she reported the assault to her university. The person in charge of investigating sexual assault claims was also in charge of investigating issues like plagiarism, which took priority. Becky had hoped she would finally receive help when the police processed the rape kit.

“When my rape kit came back six months later, the results were inconclusive,” she said. “The police weren’t going to investigate further.”

The Retaliation

Her peers not only disbelieved her, they went out of their way to cause her misery. Fellow students took to the anonymous chat room Yik Yak, Facebook groups, Twitter pages, Tumblr accounts, and Reddit threads, in droves. Social media platforms gave this gossip permanence and power, with posts about Becky Stevenson shared every 3 to 4 minutes.

“It wasn’t just a conversation about my assault anymore,” Becky said. “It was a dissection of my person.” Becky’s physical and mental health suffered from the assault and retaliation, nearly causing her to end her own life at one point.

Becky Stevenson

It wasn’t just a conversation about my assault anymore. It was a dissection of my person.

The Survivor Network

Then, something remarkable happened. Needing someone to listen, other students confided in Becky, revealing their assaults and the need for better university support. This group of survivors sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. When the university formed a Title IX office in November 2014, Becky immediately reported her situation. Reporting her assault was the first of many efforts to protect others from suffering similar heinous crimes.

After a semester abroad in Scotland, Becky returned to Texas enlightened and determined that other students would not have to endure the same ordeal she faced. Becky trained with the local advocacy center and teamed up with the Title IX coordinator as a liaison between Greek Life and the Title IX office.

While Becky was preparing for the law school entrance exam, she came across the story of another rape survivor who had bravely shared her experience publicly. Unfortunately, this survivor also faced challenges with the university’s handling of the situation regarding Title IX support.

What started as a group message on Facebook became a grassroots support group of rape survivors.

“We weren’t affiliated with the university, but we were listening to the stories of university survivors, and pretty soon, we had what I would describe as a network of survivors,” said Becky.

Becky served as an underground administrator of this sexual assault survivor support group, investing her time and energy into giving them the support she wished she would have had.

“I wanted them to know they were heard, that someone believed them, that their plight was relatable and that they didn’t have to go through it alone,” she said. “I wanted them to know they weren’t crazy for feeling the effects of trauma. It was an emotionally exhausting venture, but I learned a lot and felt fulfilled in doing it. Every ‘survivor date,’ as I’d call them, had resulted in mutual empowerment. There is so much strength in numbers and power in knowing you’re not alone. We organized events and reached a lot of people.”

I wanted them to know they were heard, that someone believed them, that their plight was relatable and that they didn’t have to go through it alone.

Then, in the spring of 2016, some of the women even felt comfortable speaking with the media. Becky remained in the background, helping them navigate the press. She eventually would give reporters anonymous information about the mishandling of rape cases, including her own.

Becky’s Advocacy Work

Becky graduated and went on to study law. “I realized that the first step I should take was going to law school to understand the brass tacks of how all of this happens, how these issues can be so overlooked, where the funding goes, even why rape cases aren’t prosecuted very much,” she said.

Becky has returned to the university as a guest lecturer nearly every semester since 2016 to educate thousands of students and several sorority executive boards on her story, consent, and Title IXs. The university has made significant progress over the past decade in fostering a safer and more inclusive learning environment. She has also spoken to hundreds of attendees at events related to human trafficking and sexual assault over the years.

“After each presentation, about three to five survivors stay after and exchange contact information with me,” said Becky. “I’ve remained in touch with all those survivors over the years.”

Today, she advocates for low-income survivors as part of our Legal Aid for Survivors of Sexual Assault Grant funded by the Texas Access to Justice Foundation. Through this grant program, she helps clients, all of whom have experienced the effects of sexual violence in their lives. With Becky’s legal advocacy, these clients are able to leave abusive situations and protect themselves and their children. Most of all, Becky hopes to empower survivors. “To me, justice is doing all I can to be the person I needed back then—and helping those who come after me find their voice,” said Becky. “Part of that is being open about this piece of my life so survivors know they aren’t alone in their fight; part of it is also standing in solidarity with and fighting for survivors who want to seek legal remedies outside the criminal justice system. I have found that the shame and isolation surrounding sexual assault begin to break down when survivors feel safe. Safety is the bedrock of empowerment: empowerment to act, empowerment to seek help, empowerment to keep living, empowerment to move forward without their trauma being a debilitating obstacle to their daily lives.”

Legal Aid for College Students

If you have yet to apply to colleges, now is the time to think critically about which schools are approaching campus sexual misconduct through a trauma-informed lens. If you are already enrolled, research the efforts made by your school to make your experience on campus safe.

As a college student, if you should ever need to seek justice against an abuser, legal aid organizations are available in every state and are a valuable resource for survivors.

- Your eligibility for legal aid is determined by your own income. Many college students qualify for free legal aid as they are typically no longer considered part of their parents’ household. Even if you are working a campus job, you may qualify for free legal aid. Seeking the assistance of an attorney can be a valuable resource to help you navigate the legal system at no cost.

- You don’t have to report the incident to the police to get help from a legal aid attorney.

- A legal aid attorney’s priority in serving survivors is to ensure personal safety at home, work, and school. For college students, home, work, and school are often one and the same.

- A legal aid attorney can help you take legal action by applying for a protective order; helping you transfer to a different school; keeping medical, mental health, and education records private; terminating a lease; applying for crime victim compensation; and fighting hospital bills or other creditors.

Title IX is not just a policy, it’s a promise – a promise to survivors of sexual assault that they will be heard, supported, and protected. Our Legal Aid to Survivors of Sexual Assault (LASSA) Team works tirelessly to uphold this promise, ensuring that justice is not just a concept, but a reality for survivors.

“We want you to know your rights,” says Becky. “Some of the strongest vehicles for change in campus safety have been the stories and actions of student survivors. You and your peers have a right to a college experience free from sexual violence.”

Some of the strongest vehicles for change in campus safety have been the stories and actions of student survivors. You and your peers have a right to a college experience free from sexual violence.

To learn more about Becky’s story, visit www.notyourjanedoe.com.

Upcoming Livestream on Campus Safety

Please join us for our next episode of The Safe Space, scheduled for April 18, 2024, at 3:00 PM CST. In honor of Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM), Staff Attorney Becky Stevenson and Supervising Attorney Brittany Hightower will engage in a live discussion on campus safety via Facebook LIVE. The Safe Space is a LASSA project and quarterly series dedicated to sharing critical information and resources to survivors of sexual assault.

Lone Star Legal Aid (LSLA) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit law firm focused on advocacy for low-income and underserved populations by providing free legal education, advice, and representation. LSLA serves millions of people at 125% of federal poverty guidelines, who live in 72 counties in the eastern and Gulf Coast regions of Texas, and 4 counties in Southwest Arkansas. LSLA focuses its resources on maintaining, enhancing, and protecting income and economic stability; preserving housing; improving outcomes for children; establishing and sustaining family safety, stability, health, and wellbeing; and assisting populations with special vulnerabilities, like those with disabilities, the aging, survivors of crime and disasters, the unemployed and underemployed, the unhoused, those with limited English language skills, and the LGBTQIA+ community. To learn more about Lone Star Legal Aid, visit our website at www.LoneStarLegal.org.

Media contact: media@lonestarlegal.org